[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Investors dip into savings to offer high-price home loans to borrowers rejected by banks.

By KIRSTEN GRIND

TARZANA, Calif.— Mike Klemens, 81 years old, is a bridge player, real-estate investor and part of a new generation of private lenders helping reshape the American home-mortgage market.

From his ranch-style house in the hills above the San Fernando Valley, he services home loans financed from his individual retirement account and profits made in 35 years of buying and selling Southern California real estate.

“Holy cow!” he said during a recent tally of his more than $3.7-million loan portfolio, which in two months this year jumped to 29 mortgages from 19. “I didn’t think it was that much.”

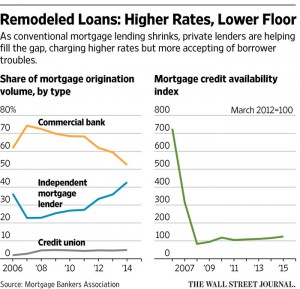

Many traditional mortgage lenders have retreated from the business since new rules and higher standards were imposed after the financial crisis. Even with real-estate prices rebounding in California and other high-demand U.S. markets, cautious banks lean toward wealthier, lower-risk borrowers.

Mr. Klemens and other upstarts are filling the vacuum. That means a small but growing slice of the mortgage market has shifted from mainstream banks to an informal, loosely regulated corner of property finance. These lenders can earn 8% and more on their money—the catch is they must stomach the risk of lending their savings to borrowers rejected by banks.

“It’s the Wild West out here,” said Corey Kohnke, 27 years old, who spends his days driving around Orange County, Calif., matching borrowers with investors looking to make loans, a job that pays commissions of 2% to 8%.

Private lenders charge annual interest rates as high as triple those of a conventional 30-year fixed-rate mortgage. Some, like Mr. Klemens, issue loans from personal fortunes and collect monthly interest payments. Others make loans and sell the note to investors. There also are private mortgage funds that pool investor money.

“We can’t make loans fast enough to sell them to our investors,” said Michelle Rodriguez, general counsel for R.C. Temme Corp., and its affiliate, private lender Woodland Hills Mortgage Corp. in Los Angeles. When the firm’s salespeople call investors to market the loans, she said, “they’re snapped up within minutes. Literally, 15 minutes and they’re gone.”

Many private lenders issue too few mortgage loans to be closely watched in the patchwork of state and federal oversight that bind banks and other larger financial institutions. They nonetheless must register with their states at a minimum. The oversight is supposed to make sure lenders don’t mislead investors or engage in deceptive practices.

“We expect all lenders to play by the rules and treat borrowers fairly,” said a spokesman for the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, which oversees lenders issuing five or more mortgages a year and is charged with protecting borrowers nationwide.

Data on the size of the private-lending industry and the number of mortgages issued are hard to come by. Many companies and individuals produce so few loans they are exempt from federal mortgage disclosures.

“The private-money industry is just that—private,” said Gordon Albrecht, a senior director at FCI Lender Services Inc. The Anaheim, Calif., company, one of the largest to service private-money home loans, estimated the market generates about $65 billion in mortgages a year. Others say more.

By comparison, mortgages in the U.S. last year totaled about $1.6 trillion, according to the Mortgage Bankers Association. Wells Fargo & Co. alone issued $43 billion in residential-mortgage loans during the first quarter of 2016, making it the largest residential lender in the U.S.

“This is a blind spot when thinking about systemic risk,” said David Min, a law professor at the University of California, Irvine, and a former attorney at the SEC. “Regulators might not be able to see that this area is growing so quickly.”

Chrissey Breault, a spokeswoman for the American Association of Private Lenders, said reports of fraud are common. Some lenders have copied the trade group’s logo onto documents to impress prospective borrowers, she said. Others appear to be issuing home mortgages in a way designed to avoid government oversight, say those in the business.

Rapid growth in private lending has attracted the interest of traditional banks. Wells Fargo and Nomura Holdings Inc. are giving credit lines to private lenders to fund more home loans, say people familiar with the matter.

“We have a few, long-standing relationships with minimal credit commitments,” a spokesman for Wells Fargo said. A spokeswoman for Nomura declined to comment.

High-stakes homework

Mr. Klemens works from an office in his home in an affluent Los Angeles neighborhood south of Ventura Boulevard. He keeps winning bridge scores taped to closet doors. He is surrounded by shelves of cookbooks, references for the hobby he enjoys with his wife.

A Boston native who originally worked in mortgage banking, Mr. Klemens moved to Southern California in 1962 and began real-estate investing in 1981. He bought low and sold high. In 1994, after the 6.7 magnitude Northridge earthquake depressed real-estate prices in the surrounding San Fernando Valley, he opened his wallet. He eventually owned 47 properties, he said, with the majority sold at a profit in 2005 and 2006—before the financial crisis sent prices plummeting. He kept 11 properties.

PHOTO: DAVID WALTER BANKS FOR THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

Financing an entire mortgage brings higher risk and better returns. The more a lender loans on a mortgage, the higher its loan-to-value ratio and risk. The lender is entitled to take back the property if borrowers fall behind on payments but foreclosures can take a year or longer.

On a recent afternoon, he booted up his AOL account on his desktop computer and read through a listing of loans offered for purchase: a $685,000 mortgage with a 10.5% interest rate and a loan-to-value ratio of 70%; a $360,000 condo loan with an 8.5% rate and a loan-to-value ratio of 53%.

The list featured a short description of the property and loan terms. Mr. Klemens said the loan-to-value ratios are too high. Other factors he considers: the property, the neighborhood and, sometimes, a face-to-face meeting.

His borrowers typically have one or more flaws that keep them from getting a bank loan. Maybe they can’t document their income, he said, or have a poor credit history. He relies on experience to determine who is a good bet. “If I can interface directly with the borrower,” he said, “I can know what’s cooking.”

Bank loan standards, Mr. Klemens said, are “very cookie-cutter right now. They won’t ever think outside the box.”

He and his wife, Nancy, service some of the mortgages at home. Each month, Mrs. Klemens prints out bills and mails them to some borrowers. Mr. Klemens crosses off loan payments with a highlighter pen when checks arrive.

Mr. Klemens said his borrowers rarely fall behind. When one did, he said, he initiated a foreclosure after 35 days and the borrower paid up.

“It taught him a lesson,” he said.

The average time for a foreclosure proceeding in the U.S. is 629 days, according to research firm RealtyTrac.

Oversight avoidance

Federal regulations by the CFPB require that traditional mortgages—for houses where borrowers are going to reside—comply with rules intended to make sure people can afford the loan.

But some lenders have found a loophole. If the mortgage is for a business purpose, a loosely defined category that includes investment properties, borrowers lose protections, such as the ability to sue under CFPB rules.

Ms. Rodriguez, of private lender Woodland Hills Mortgage, said she has recently seen several applications from borrowers seeking to refinance their home mortgages that had been labeled business-purpose loans by the original lender.

Those borrowers have told Ms. Rodriguez, “ ‘Oh, they told me to say that,’ ” she recalled. Other lenders reported similar instances.

PHOTO: DAVID WALTER BANKS FOR THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

Most private lenders rely on word-of-mouth referrals, but the website of private lender Athas Capital Group Inc. advertises to borrowers and brokers. On a recent day, they offered interest rates of 6.99% to 8.99% on one type of subprime mortgage and loan approvals within four hours.

A picture of a multimillion-dollar home with a stone-and-wood facade is captioned: “If you have a customer that has a Trophy Home and has been turned down by the banks, we want to lend to them!”

Private mortgage funds based in California are expected to register with the state for an investment adviser license.

In 2013, California regulators ordered Rama Capital Partners—the managing member of private mortgage fund Rama Fund, an affiliate of Athas, of Calabasas, Calif.—to “desist and refrain” from unlicensed activities because it failed to obtain an investment-adviser registration, a violation of state law, state documents said. In a settlement, Rama didn’t agree to any wrongdoing and paid $35,000.

Tom Dresslar, a spokesman for the California Department of Business Oversight, said the fund then obtained a license that was withdrawn in late 2015. Rama currently has about 600 accredited investors, according to the company.

“Licensing of investment advisers is important because it at least provides a measure of assurance that firms and individuals are on the up and up,” Mr. Dresslar said.

Athas and Rama’s co-chief executive, Brian O’Shaughnessy, said in an April 28 interview that the administrative action by the state was the result of a mix-up and that all fund licenses were in order. That same day, Rama applied for a new license with the state, according to Mr. Dresslar.

Alim Kassam, co-chief executive officer of Athas and Rama, said Rama had been planning for months to renew its California investment adviser registration and that it was “100% coincidence” that it happened the day of an inquiry from The Wall Street Journal.

Private lending surfaced in the 1940s, riding the ups and downs of postwar California real estate. These so-called hard-money lenders mostly served property developers and businesses, still the bulk of work for such entrepreneurs as Mr. Klemens. They have long supplied short-term loans to investors buying rundown or underpriced properties to fix up for a quick sale.

Tighter lending standards by banks have shrunk the traditional mortgage business. That has turned out to be good news for such longtime private lenders as David Herzer in Redwood City, Calif. Home buyers turned away by conventional lenders—because of, say, gaps in their work history or a recent divorce—can prove to be reliable borrowers, he said.

“Often times, the reason that the bank doesn’t want to do a loan is pretty silly,” Mr. Herzer said. “I can capture what can effectively be a bank loan and charge private money rates.”

In Los Angeles, Joffrey Long said he started investing in mortgages because he didn’t want all of his money tied up in properties. He buys mortgages or slices of them through private lenders like R.C. Temme Corp. that promise yields of 5.5% to 9%.

“There’s huge investor interest,” Mr. Long said. “People are afraid of the stock market.”

Anthony Geraci, a lawyer in Irvine, Calif., said he has helped clients form five new private mortgage funds in the past year. “That doesn’t sound like a lot,” he said. “But before that it was zero.”

Borrower Terry Lewis, a single mother of five grown children, said she spent months searching for a lender willing to refinance the second mortgage on her four-bedroom, 1,700-square-foot house in Burbank, Calif.

Ms. Lewis missed two payments to the lender of her second mortgage, Citadel Servicing Corp. She said the company initiated foreclosure proceedings and she had to find another lender or risk losing her house. A Citadel spokesman declined to comment.

Ms. Lewis, executive director of Los Angeles County’s Mental Health Commission, said she has built up substantial equity over the 22 years she has owned the house, which she estimated was worth $600,000.

A recent divorce and subsequent bankruptcy left her with a low credit score and loan rejections by several banks and her credit union. Ms. Lewis then found Marquee Funding Group Inc., a private lender in Calabasas, Calif.

The company took a few days to approve a loan of about $100,000 that carried a 10% interest rate.

The long hunt “was very, very trying, and I was very depressed and anxious,” said Ms. Lewis, 60 years old. “I’m OK now.”

Write to Kirsten Grind at [email protected]

For additional information, please visit www.jcap.net.

About Jcap Private Lending

JCAP Private Lending is a Direct Lender who closes and services Investor Funded Short-Term Real Estate Loans. Our experienced team has been providing quality mortgage services for over 30 years. JCAP Private Lending is an Asset Based Lender who steps in to quickly solve a short-term financial need secured by Real Estate. JCAP has an innovative approach to lending, focusing on speed, simplicity, and safety for borrowers and investors. JCAP’s operating philosophy is defined by the simple but impactful statement — “We Care & We Serve”.

Located in Newport Beach, CA, JCAP Private Lending primarily lends Hard Money & Private Loans secured by 1st & 2nd TD’s on residential property in Coastal California. For further information, please visit www.jcap.net.

For inquiries, please contact:

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/1″][vc_social_links size=”normal” linkedin=”https://www.linkedin.com/in/bob-eakin-4778748a”][/vc_column][/vc_row]